‘Dark oxygen’ mission takes aim at other worlds

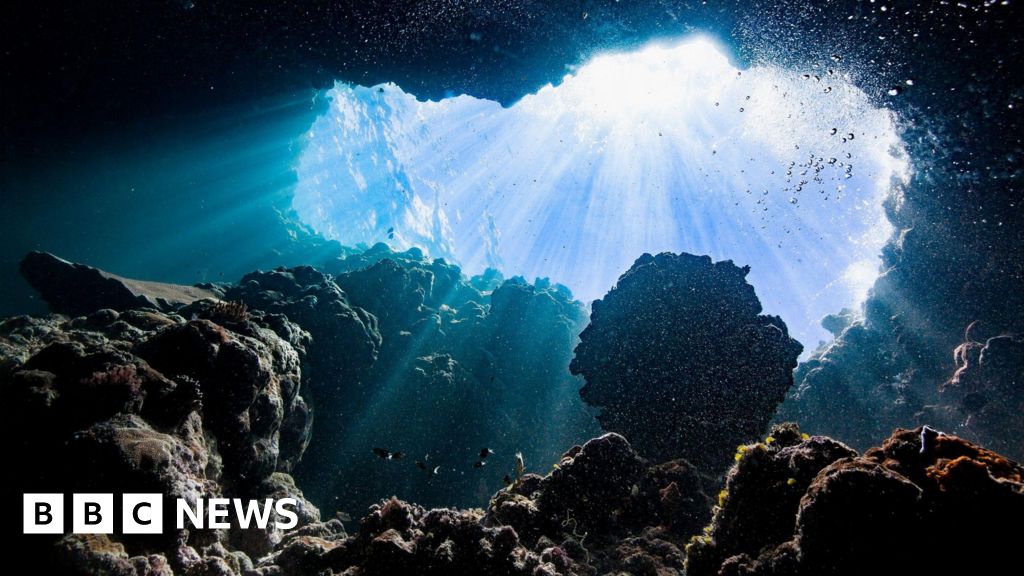

Scientists who recently discovered that metal lumps on the dark seabed make oxygen, have announced plans to study the deepest parts of Earth’s oceans in order to understand the strange phenomenon.

Their mission could “change the way we look at the possibility of life on other planets too,” the researchers say.

The initial discovery confounded marine scientists. It was previously accepted that oxygen could only be produced in sunlight by plants – in a process called photosynthesis.

If oxygen – a vital component of life – is made in the dark by metal lumps, the researchers believe that process could be happening on other planets, creating oxygen-rich environments where life could thrive.

Lead researcher Prof Andrew Sweetman explained: “We are already in conversation with experts at Nasa who believe dark oxygen could reshape our understanding of how life might be sustained on other planets without direct sunlight.

“We want to go out there and figure out what exactly is going on.”

The initial discovery triggered a global scientific row – there was criticism of the findings from some scientists and from deep sea mining companies that plan to harvest the precious metals in the seabed nodules.

If oxygen is produced at these extreme depths, in total darkness, that calls into question what life could survive and thrive on the seafloor, and what impact mining activities could have on that marine life.

That means that seabed mining companies and environmental organisations – some of which claimed that the findings provided evidence that seafloor mining plans should be halted – will be watching this new investigation closely.

The plan is to work at sites where the seabed is more than 10km (6.2 miles) deep, using remotely-operated submersible equipment.

“We have instruments that can go to the deepest parts of the ocean,” explained Prof Sweetman. “We’re pretty confident we’ll find it happening elsewhere, so we’ll start probing what’s causing it.”

Some of those experiments, in collaboration with scientists at Nasa, will aim to understand whether the same process could allow microscopic life to thrive beneath oceans that are on other planets and moons.

“If there’s oxygen,” said Prof Sweetman, “there could be microbial life taking advantage of that.”

The initial, biologically baffling findings were published last year in the journal Nature Geoscience. They came from several expeditions to an area of the deep sea between Hawaii and Mexico, where Prof Sweetman and his colleagues sent sensors to the seabed – at about 5km (3.1 miles) depth.

That area is part of a vast swathe of seafloor that is covered with the naturally occurring metal nodules, which form when dissolved metals in seawater collect on fragments of shell – or other debris. It’s a process that takes millions of years.

Sensors that the team deployed repeatedly showed oxygen levels going up.

“I just ignored it, Prof Sweetman told BBC News at the time, “because I’d been taught that you only get oxygen through photosynthesis”.

Eventually, he and his colleagues stopped ignoring their readings and set out instead to understand what was going on. Experiments in their lab – with nodules that the team collected submerged in beakers of seawater – led the scientists to conclude that the metallic lumps were making oxygen out of seawater. The nodules, they found, generated electric currents that could split (or electrolyse) molecules of seawater into hydrogen and oxygen.

Then came the backlash, in the form of rebuttals – posted online – from scientists and from seabed mining companies.

One of the critics, Michael Clarke from the Metals Company, a Canadian deep sea mining company, told BBC News that the criticism was focused on a “lack of scientific rigour in the experimental design and data collection”. Basically, he and other critics claimed there was no oxygen production – just bubbles that the equipment produced during sample collection.

“We’ve ruled out that possibility,” Prof Sweetman responded. “But these [new] experiments will provide the proof.”

This might seem a niche, technical argument, but several multi-billion pound mining companies are already exploring the possibility of harvesting tonnes of these metals from the seafloor.

The natural deposits they are targeting contain metals vital for making batteries, and demand for those metals is increasing rapidly as many economies move from fossil fuels to, for example, electric vehicles.

The race to extract those resources has caused concern among environmental groups and researchers. More than 900 marine scientists from 44 countries have signed a petition highlighting the environmental risks and calling for a pause on mining activity.

Talking about his team’s latest research mission at a press conference on Friday, Prof Sweetman said: “Before we do anything, we need to – as best as possible – understand the [deep sea] ecosystem.

“I think the right decision is to hold off before we decide if this is the right thing to do as a a global society.”